- Every year, about 14-million women lose so much blood during childbirth that they could die; about 70 000 do.

- The condition is called postpartum haemorrhage — but it can be stopped if health workers realise in time that a new mother is bleeding too much and can act in time.

- Until now there’s not been a standard way of knowing when blood loss is getting dangerous and what needs to be done. But new recommendations from the World Health Organisation are changing that — and saving lives.

- Health workers from a hospital in Kenya write about what they’ve experienced in their labour ward.

In today’s newsletter, Linda Pretorius explains why measuring blood loss during childbirth helps nurses and midwives reduce deaths from postpartum bleeding. Sign up.

COMMENT

In the labour ward at the Malindi Sub-County Hospital, situated in the Kilifi county along the east coast of Kenya, necessity is the mother of invention.

For three years, my colleagues and I participated in an international study that evaluated a treatment approach called E-MOTIVE to help women who’ve just given birth from losing too much blood.

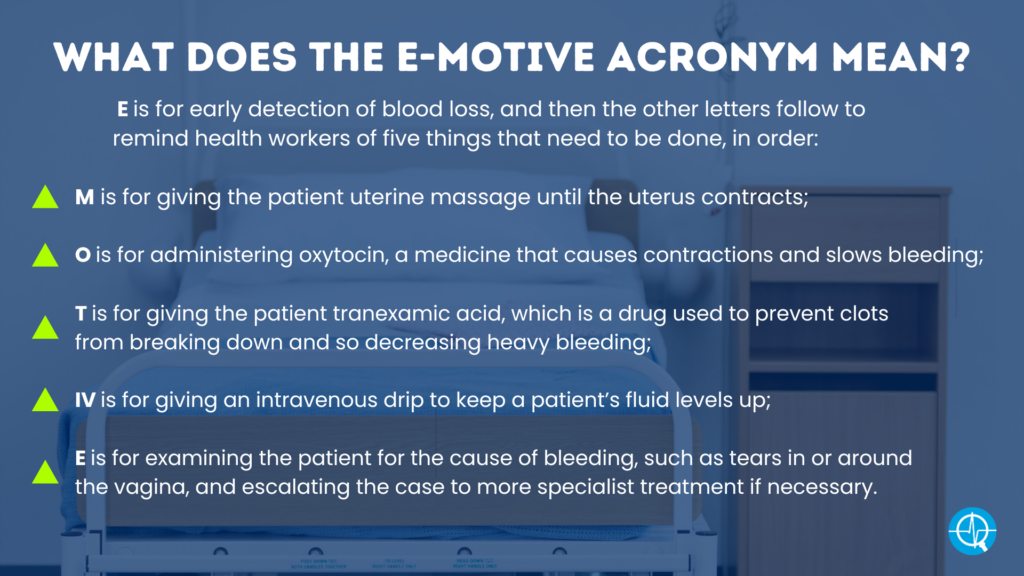

Bhekisisa previously reported that the package of care starts with measuring how much blood a new mother loses after giving birth using a “drape” — a plastic, funnel-like sheet that collects the blood into a volume-marked pouch. If this gets to 500ml, or if it gets up to 300ml and the woman’s blood pressure is dropping or her heart rate is picking up, the nurse or midwife should start a bundle of five things to stop the bleeding.

Losing more than half a litre of blood or more in 24 hours after giving birth is called postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). It happens to 14-million women every year, with one dying every six minutes because of it, the World Health Organisation (WHO) says — because of a range of contributing factors, one of which is that visual estimation of blood lost is known to be inaccurate.

Soon after learning how to implement the approach, we realised it’s a lifesaver at our hospital. Being able to accurately measure blood loss helps with diagnosing PPH in time. The study showed that acting on the diagnosis reduced PPH, deaths or the need for surgery by 60%.

But when the trial ended, we stopped receiving the commodities that were needed to conduct the study. Not least were the imported blood-collecting drapes.

Keeping moms safe

So, my colleagues invented their own drape-like apron made from waterproof hospital mattress pads that we had on hand in our hospital and stitched by a local tailor, which funnels blood into a pan with calibrated markings.

Their makeshift solution shows how much they believe in this management approach. In fact, they had wholeheartedly embraced it even before the results of the trial of the WHO’s first-response bundle for PPH were published.

The WHO has since also published new recommendations that set out standardised guidelines about what signs health workers should look for to identify PPH and how it should be treated, so that women everywhere get the same treatment — and can get more specialised care if needed. Further, the WHO states that a clear plan for making the approach work must be available, such as training health staff where they work and having all the needed supplies on hand.

While each individual component of the E-MOTIVE treatment previously had been studied and recommended for all women with PPH, the bundle approach — meaning doing the five things as a set — had not been studied or recommended.

My role in the E-MOTIVE research project was to train colleagues on providing the care as a series and supervising them as they worked. Scepticism on the part of some, or resistance to doing things differently from before (for example, doing only one of the five things or choosing to refer the case to a doctor from the start) evaporated when we saw just how effective the bundle approach is when combined with early detection using the drapes.

Putting the approach into practice resulted in two or three new mothers every week experiencing excessive blood loss in our labour ward, instead of five or six as before.

The death of a mother has devastating consequences for her family and community. Research shows that a newborn whose mother died before they were six months old, for example during childbirth, is five times more likely to die before they can become adults than those whose moms survive.

The loss of a mother has knock-on effects for children’s nutrition and education, and also affects things like gender equality — which all slows the world’s progress in getting to a sustainable, healthy and prosperous future, as set out by the United Nations sustainable development goals.

No more guesswork

But nurses, midwives and other health workers, as new mothers’ caregivers, also suffer when a patient dies.

It’s demoralising and draining to work tirelessly to keep women safe during childbirth yet still lose so many to a preventable condition such as PPH. Unlike patients who are clearly very ill, these young women often look well — they’re breastfeeding, smiling and joking with staff and their families.

Then suddenly, in the next moment, they’re in the throes of the life-threatening crisis of severe bleeding after birth. It’s chilling and shocking.

Midwives like us, who have first-hand experience of implementing the bundle, also feel newly empowered. We no longer need to summon doctors in a panic when a woman is bleeding excessively. With the bundle, we can confidently and competently manage most cases of PPH, leaving doctors with more time to tend to other cases needing their expertise.

And because we learned how to apply the approach along with nurses and doctors, a respectful sense of teamwork emerged. Doctors now seem less likely to demand that we defend our clinical judgement and are less inclined to ask, “Why did you give tranexamic acid?”

In the past this may have been a valid question by a doctor. We know now that giving women this drug in time to stop heavy bleeding is a crucial step of the treatment bundle. While health facilities in Kenya may have this medicine on hand, it’s usually bought and reserved for other purposes, like trauma cases, and not routinely used for management of PPH.

We know that the bundle works — but only when it’s started on time and all the supplies needed for it are available, including drapes and drugs like tranexamic acid. Hospital administrators and procurement officers need to be made aware of what the E-MOTIVE bundle can mean for keeping women safe during childbirth, as should health ministries, which have the power to update policy recommendations.

If all my colleagues are trained to implement the bundle and have all the necessary commodities, I think that my country could reduce severe PPH by even more than 60% — maybe as much as 80%. So too could your country — and that will be a big achievement to ensure a thriving future generation.

Isabella Ochieng, a nurse midwife and maternal and newborn health technical advisor for Jhpiego, worked on the E-MOTIVE trial.